El Baile

Flamenco dance, or el baile, is more than rhythm and choreography. It is a language of the body, a visual expression of emotions that often defies words. For those new to flamenco, dance may be the most immediate and captivating entry point, with its footwork, sweeping arms, and powerful presence. But behind each gesture is a legacy of centuries, a deep cultural heritage carried in every movement.

(With my original interpretations and restructured content, this article is based on insights from "Guía del Flamenco" by Luis López Ruiz.)

1. Why Dance Exists in Flamenco

Flamenco dance—like all forms of deep artistic expression—was born out of an urgent need to release emotion. Someone, somewhere, driven by an internal wave of feeling, simply had to move. And so, dance was born—spontaneously and instinctively.

While flamenco dance (el baile) doesn’t have a single clear origin, it emerged as a gypsy-infused adaptation of pre-existing rhythmic expressions. From the 15th century onward, the fusion of Andalusian and Gitano cultures gave birth to something new: danceable forms rooted in Andalusian folk music, now transformed with gypsy character and intensity.

The Andalusians have always had a natural, almost genetic rhythm—a kind of innate musicality. Classical authors, like Avieno in his Oda Marítima, praised the remarkable sense of rhythm among the people of Baetica (ancient Andalusia). That rhythmic instinct became the foundation of flamenco dance.

Though not exclusive to any one culture, the Gitano contribution to flamenco dance is undeniable. Their unique flair, improvisation, and natural sense of expression shaped flamenco’s essence. For Gitanos, dance isn’t something learned—it’s something felt. They dance because they must, because it’s in their blood, and they do it with a freedom and fire that formal training can never replicate.

2. Early Mentions and Literary References

The earliest written references to dance in Spain, particularly the dance of the Gitanos, begin to appear around the 16th century. Figures like Gil Vicente alluded to it, followed by renowned writers such as Lope de Vega and Cervantes. By the 18th century, Ramón de la Cruz made mention of seguidillas gitanas in his works.

However, it’s important to note that these early references don’t explicitly mention flamenco as we know it today. Rather, they refer to a broader category of Spanish popular music and dance, which was often interpreted with a gypsy flair. These mentions reflect a growing awareness of a uniquely expressive and rhythmic dance style, but not yet the formalized flamenco dance tradition.

The first clear literary reference to flamenco dance appears in 1847, in Escenas andaluzas by Serafín Estébanez Calderón. In the chapter titled Un baile en Triana, he describes a flamenco gathering and names actual singers and dancers who were already part of the flamenco world. It’s in this moment that flamenco dance begins to be recognized as a distinct cultural form, rooted in Andalusian soil and shaped by the Gitano spirit.

While it’s tempting to imagine flamenco dance as ancient, the truth is that no concrete evidence places it before the 18th century. Until proven otherwise, we must respect that historical limit, even while honoring the deep and diverse traditions that helped shape it.

3. Characteristics of Flamenco Dance

Flamenco dance captivates, especially for those unfamiliar with the art form. Its expressive nature, visual power, and rhythmic force make it immediately accessible and emotionally impactful. Unlike cante, which is intimate and often melancholic, flamenco dance is bold, extroverted, and full of movement—it appeals to both the eyes and the ears, offering a complete sensory experience.

Audiences are often drawn to the dancer’s movements: the striking posture, sharp turns, rapid footwork (zapateado), arm flourishes, and expressive gestures of the torso and hands. These create a powerful stage presence that can dominate even the loudest voice or guitar solo. This is especially evident in commercial venues or tourist tablaos, where dance is often the main attraction.

When analyzing flamenco dance individually, we notice that traditionally male dancers emphasize upright posture, firm footwork, and restrained arm movements. Female dancers, on the other hand, often showcase greater fluidity in their upper body, especially the arms and hands, while executing dynamic and complex rhythms with the feet. Over time, gender distinctions in flamenco have blurred, and contemporary dancers of all genders explore a wide range of movement, expression, and even androgynous styling.

At its core, flamenco dance demands more than technical precision—it requires duende, that ineffable, emotional force that brings the dance to life. Grace (garbo), elegance, personality, and soul are essential. Technical brilliance without emotional depth risks becoming cold and uninspired.

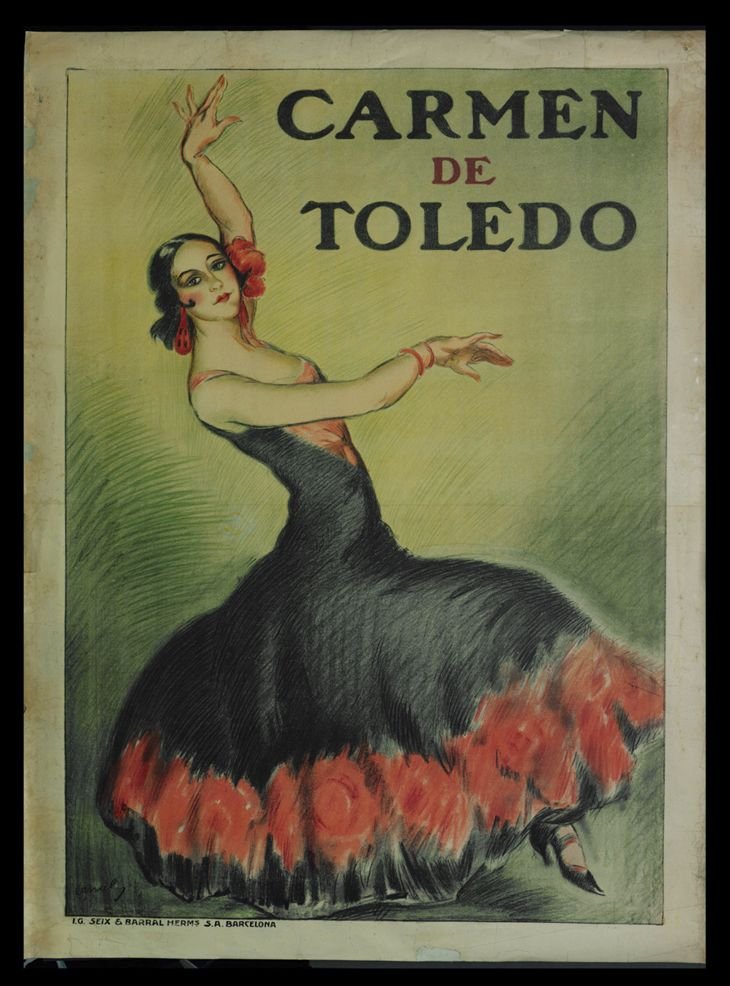

Costuming in flamenco has evolved with performance demands. In the 19th century, dancers often performed in their street clothes, but today’s attire is far more theatrical. Women wear long, voluminous skirts with extended trains (bata de cola), enhancing their silhouette and becoming part of the choreography. Mastering the bata de cola requires strength, coordination, and elegance. For men, modern styles emphasize tailored pants, close-fitting jackets, and often dark tones to highlight form and gesture with clarity.

Finally, flamenco dance is not about exaggerated acrobatics or large, dramatic movements across the stage. Some of the most powerful dancers barely leave their spot, relying instead on a tightly woven series of gestures, rhythmic flourishes, and expressive stillness. It’s not about how much space is covered, but how much meaning is conveyed.

4. Gesture, Presence, and Costume

The dancer’s command of space and ability to communicate through movement is key. Flamenco is not about doing many steps quickly—it is about presence. Some of the most powerful moments come in stillness, in a single pause that says everything.

Costumes in flamenco also play a significant role in visual storytelling. Over time, the costumes have evolved from everyday clothing to theatrical, stylized outfits. For women, dresses became more voluminous and were often adorned with ruffles, shawls, and accessories like flowers or fans. For men, fitted jackets and high-waisted pants emphasized a strong silhouette. These styles added drama and distinction to performances, but they also responded to the needs of the stage and the demands of commercial performance.

José Greco and Lola de Ronda, 1956.

5. Danceable and Non-Danceable Palos

Not all flamenco songs are meant to be danced. Traditional classifications separate the palos into those commonly danced and those typically sung only. These include:

a) Cantes a palo seco – deep songs like martinete, often unaccompanied and not intended for dance.

b) Fandangos and cantes de Levante – including mineras, malagueñas, cartageneras, and jabaras; some of these have dance adaptations.

c) Folk-influenced or non-traditional songs – such as nanas, marianas, and campanilleros, which are not typically danced but may sometimes be choreographed.

d) Cantes de ida y vuelta – styles like guajiras, milongas, and vidalitas, which have Latin American roots and are often danced today.

While traditional guidelines exist, many modern choreographers choose to reinterpret these boundaries. Still, a deep understanding of each palo’s emotional and rhythmic structure is essential to preserve authenticity in performance.

6. The Importance of Space and Pace

There’s a widespread misconception that more movement means better dancing. In reality, flamenco’s power often comes from stillness, tension, and precise pacing. True artistry in dance is not about speed, but about knowing how to fill the space with emotion and intention.

Modern flamenco sometimes falls into the trap of rushing or over-choreographing, losing the soul of the dance. As Manuela Carrasco said, “Flamenco is art, personality, and knowing when to stop.” The ability to pause—to wait, to let the moment breathe—is a mark of a mature dancer. Mastery comes not only in movement but in restraint.

It’s also important to note that dance isn’t a showcase of tricks or acrobatics. The magic of flamenco lies in its honesty, its vulnerability, and its power to create a shared emotional space with the audience. A dancer’s movement should be deliberate, connected to the music, and reflective of the cante’s emotional weight. This grounded approach makes flamenco dance feel timeless and deeply human.

7. Final Thoughts

Flamenco dance is a visceral extension of the cante. You can sing flamenco without dancing, but you cannot truly dance flamenco without the song. The dancer gives the cante a body, turning voice into motion and rhythm into fire.

Dance, then, is not a separate art but a living echo of the singer’s voice. The body becomes a second instrument—one that speaks in silence, shouts with a stomp, and weeps with a turn of the wrist. When flamenco is danced well, we feel it in our bones. It is not about impressing the audience, but about revealing truth.

To all dancers and students: let this remind you that every gesture counts. Practice technique, but never lose the emotion. Learn the forms, but always seek the duende. The future of flamenco depends not only on how well you dance, but on how deeply you feel.

El baile is a conversation with your ancestors, a celebration of your culture, and a mirror of your soul. As you step into the studio or onto the stage, remember you are carrying a tradition that has survived through feeling. That is your inheritance—and your responsibility.

In flamenco, the singer lights the flame—but the dancer makes it burn. Let your dance be a fire worth remembering.